The only 4 Olympic medals in the country have come from women. In addition, they have won 9 of the 13 Olympic diplomas in the country. Throughout the history of Olympic sport for Costa Rica, female athletes tend to achieve the best national participation.

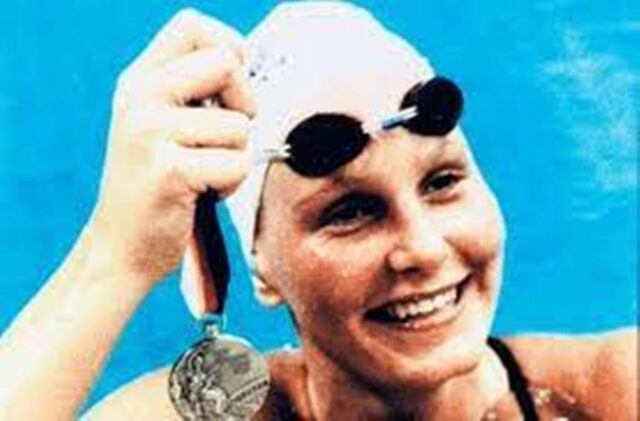

The 4 medals of sisters Sylvia and Claudia Poll Ahrens, both swimmers, between Seoul 1988 and Sydney 2000, are just the tip of the iceberg and the most visible and celebrated achievement throughout the entire Olympic history of the country, which began with a single participation in Berlin 1936, but then continued with an uninterrupted period from Tokyo 1964 to date.

However, to this record of more notorious triumphs we must add the Olympic diplomas, which are distinctions given to those who finish in the first 8 positions by sex (except in horse riding, where men and women of all ages compete on equal terms. ) or mass categories (where applicable, whether in contact sports or weightlifting).

Historial recount

Throughout history, Costa Rica has obtained 13 Olympic diplomas; 9 of them were won by female athletes, being the Poll sisters the ones who have harvested the most -with 8 altogether and 4 each- because to the diploma with silver decoration that came with the medal of that same metal obtained by Sylvia, we must add another 3 between Seoul 1988 and Barcelona 1992; While Claudia, in addition to the gold and bronze decorations for her 3 medals in those metals, added another in Atlanta 1996. Now, they were joined by the surfer Brissa Hennessy in Tokyo 2020, thanks to the fifth place in this discipline.

“I come from a family team in Puriscal, my mother (Dixiana Mena, who is also a coach), Noelia (a marcher) and I have had a hard time reaching the Olympic Games. For this reason, today I urge that all of Costa Rica believe in the talent of women”, Andrea Vargas.

Although the swimmer María del Milagro Paris had achieved a seventh place in Moscow 1980, that did not translate into an Olympic diploma, since at that time this award covered up to sixth place, and it was not until Los Angeles 1984 when it included seventh and eighth place.

For his part, prior to Kenneth Tencio’s fourth place in the newly incorporated BMX Freestyle cycling park category, the only 2 men who had achieved an Olympic diploma had been cyclist Andrés Brenes, for sixth place in mountain biking, in Atlanta 1996, and the taekwondo player Kristopher Moitland, in Beijing 2008, also finishing in that position in the men’s +80 kg category. In addition, there was only one collective representation that reached this diploma, and it was the U23 men’s soccer team, after finishing eighth in Athens 2004.

But how expensive is a pass to these jousts? What is the level of sacrifice they must make to reach the top of a long process that usually takes 4 years, after overcoming local, national, regional and continental filters?

Results of effort

During a discussion organized by the Saprissa Foundation and the United States Embassy, the winner of the first Olympic medal in history in South Korean territory explained how her success came about. “It really was the culmination of many years of effort, of training in difficult circumstances where she trained 4-5 hours a day, and a lot of planning, perseverance and discipline. It was not done overnight, but was planned 6 to 7 years before, when there was talk about the possibility of going to the Olympics and what that meant”.

The medalist even explained that she never needed to move abroad or hire any foreign coach. “I always trained in Costa Rica, I was trained by a Costa Rican coach, Francisco Rivas, and all my life at the Cariari Club. A typical routine for me was getting up at 3 a.m. My mother took me to the pool, I had been in the gym for half an hour, I swam for 2 hours from 4 to 6 am, I went home, had breakfast, went to school all day, did some homework, ate something and went to train again, from 4 to 6:30 pm, and she would come home to do homework and sleep, because she was so exhausted.

He did that on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; and during school vacations I trained double session from Monday to Saturday. But, in exchange for that, I had exceptional experiences; I competed in very nice parts around the world. I learned that one is not born for something; my parents had never played sports and we (she and Claudia) fell into swimming by accident, but it was at the point of a lot of effort and daily training (how we got far); not for being tall or of German blood. One has to be persistent, constant and fall in love with things”.

Even the oldest of the Poll sisters denied that she had been a professional swimmer. “I never made money with swimming, I never earned a salary as a footballer or other professional athletes (…). I learned what teamwork is, because to get to where I got I had to have the humility to accept that I did not do it alone, but for my mother, my coach, my teammates, my classmates and school teachers”.

Believe in the talent

For her part, the 100-meter hurdles runner, Andrea Vargas, told her story after she was a little short of being able to enter that very final, and reiterated her call to believe in female talent for sports and any other activity in general. “I come from a family team in Puriscal, my mother (Dixiana Mena, who is also a coach), Noelia (a marcher) and I have had a hard time reaching the Olympic Games. For this reason, today I urge that all of Costa Rica believe in the talent of women”.

During the press conference after her participation, organized by the National Olympic Committee, both Vargas and her coach and her mother, Mena, denied that the shortage of international fires for these jousts would affect the final. “In December she had a physical problem, I attribute more to that period in which we could not work 100% for not reaching the final. Due to the COVID issue and protecting Andrea, we renounce several international blanks; and many other blanks were canceled. Furthermore, we couldn’t play with her health, we needed to get to the Olympics healthy, so they were part of our decisions to take care of the athlete”, were Mena’s words.

“I do not put much mind into the number of blanks I need to reach a maximum cap. Rather, if we play too hard we could not reach the most important championship of the year with the performance we want”, added the eldest Vargas.

In the same vein, Brissa Hennessy also moved, who claimed that beyond her personal goals, what she cared most about is serving as inspiration for future surfers. “I came to the Olympics with the dream of winning a medal and making Costa Rica proud and inspiring a girl to jump into the ocean. I did not win a medal, but I came out with something else (…) A motivation for why I surf and how unity and support is the strongest power of all”.

The only 4 Olympic medals in the country have come from women. In addition, they have won 9 of the 13 Olympic diplomas in the country. Throughout the history of Olympic sport for Costa Rica, female athletes tend to achieve the best national participation.

The 4 medals of sisters Sylvia and Claudia Poll Ahrens, both swimmers, between Seoul 1988 and Sydney 2000, are just the tip of the iceberg and the most visible and celebrated achievement throughout the entire Olympic history of the country, which began with a single participation in Berlin 1936, but then continued with an uninterrupted period from Tokyo 1964 to date.

However, to this record of more notorious triumphs we must add the Olympic diplomas, which are distinctions given to those who finish in the first 8 positions by sex (except in horse riding, where men and women of all ages compete on equal terms. ) or mass categories (where applicable, whether in contact sports or weightlifting).

Historial recount

Throughout history, Costa Rica has obtained 13 Olympic diplomas; 9 of them were won by female athletes, being the Poll sisters the ones who have harvested the most -with 8 altogether and 4 each- because to the diploma with silver decoration that came with the medal of that same metal obtained by Sylvia, we must add another 3 between Seoul 1988 and Barcelona 1992; While Claudia, in addition to the gold and bronze decorations for her 3 medals in those metals, added another in Atlanta 1996. Now, they were joined by the surfer Brissa Hennessy in Tokyo 2020, thanks to the fifth place in this discipline.

“I come from a family team in Puriscal, my mother (Dixiana Mena, who is also a coach), Noelia (a marcher) and I have had a hard time reaching the Olympic Games. For this reason, today I urge that all of Costa Rica believe in the talent of women”, Andrea Vargas.

Although the swimmer María del Milagro Paris had achieved a seventh place in Moscow 1980, that did not translate into an Olympic diploma, since at that time this award covered up to sixth place, and it was not until Los Angeles 1984 when it included seventh and eighth place.

For his part, prior to Kenneth Tencio’s fourth place in the newly incorporated BMX Freestyle cycling park category, the only 2 men who had achieved an Olympic diploma had been cyclist Andrés Brenes, for sixth place in mountain biking, in Atlanta 1996, and the taekwondo player Kristopher Moitland, in Beijing 2008, also finishing in that position in the men’s +80 kg category. In addition, there was only one collective representation that reached this diploma, and it was the U23 men’s soccer team, after finishing eighth in Athens 2004.

But how expensive is a pass to these jousts? What is the level of sacrifice they must make to reach the top of a long process that usually takes 4 years, after overcoming local, national, regional and continental filters?

Results of effort

During a discussion organized by the Saprissa Foundation and the United States Embassy, the winner of the first Olympic medal in history in South Korean territory explained how her success came about. “It really was the culmination of many years of effort, of training in difficult circumstances where she trained 4-5 hours a day, and a lot of planning, perseverance and discipline. It was not done overnight, but was planned 6 to 7 years before, when there was talk about the possibility of going to the Olympics and what that meant”.

The medalist even explained that she never needed to move abroad or hire any foreign coach. “I always trained in Costa Rica, I was trained by a Costa Rican coach, Francisco Rivas, and all my life at the Cariari Club. A typical routine for me was getting up at 3 a.m. My mother took me to the pool, I had been in the gym for half an hour, I swam for 2 hours from 4 to 6 am, I went home, had breakfast, went to school all day, did some homework, ate something and went to train again, from 4 to 6:30 pm, and she would come home to do homework and sleep, because she was so exhausted.

He did that on Monday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; and during school vacations I trained double session from Monday to Saturday. But, in exchange for that, I had exceptional experiences; I competed in very nice parts around the world. I learned that one is not born for something; my parents had never played sports and we (she and Claudia) fell into swimming by accident, but it was at the point of a lot of effort and daily training (how we got far); not for being tall or of German blood. One has to be persistent, constant and fall in love with things”.

Even the oldest of the Poll sisters denied that she had been a professional swimmer. “I never made money with swimming, I never earned a salary as a footballer or other professional athletes (…). I learned what teamwork is, because to get to where I got I had to have the humility to accept that I did not do it alone, but for my mother, my coach, my teammates, my classmates and school teachers”.

Believe in the talent

For her part, the 100-meter hurdles runner, Andrea Vargas, told her story after she was a little short of being able to enter that very final, and reiterated her call to believe in female talent for sports and any other activity in general. “I come from a family team in Puriscal, my mother (Dixiana Mena, who is also a coach), Noelia (a marcher) and I have had a hard time reaching the Olympic Games. For this reason, today I urge that all of Costa Rica believe in the talent of women”.

During the press conference after her participation, organized by the National Olympic Committee, both Vargas and her coach and her mother, Mena, denied that the shortage of international fires for these jousts would affect the final. “In December she had a physical problem, I attribute more to that period in which we could not work 100% for not reaching the final. Due to the COVID issue and protecting Andrea, we renounce several international blanks; and many other blanks were canceled. Furthermore, we couldn’t play with her health, we needed to get to the Olympics healthy, so they were part of our decisions to take care of the athlete”, were Mena’s words.

“I do not put much mind into the number of blanks I need to reach a maximum cap. Rather, if we play too hard we could not reach the most important championship of the year with the performance we want”, added the eldest Vargas.

In the same vein, Brissa Hennessy also moved, who claimed that beyond her personal goals, what she cared most about is serving as inspiration for future surfers. “I came to the Olympics with the dream of winning a medal and making Costa Rica proud and inspiring a girl to jump into the ocean. I did not win a medal, but I came out with something else (…) A motivation for why I surf and how unity and support is the strongest power of all”.