Many researchers, including journalists, geographers, and historians of Costa Rica, have written about the railroad, specifically to the Caribbean, and everything that led to its construction: loans, delays, contracts, and even corruption.

Despite everything, the railroad was a fact. It was in operation, generating benefits for Costa Ricans not only in terms of transportation but also in terms of economic growth, tourism, and culture.

In the history before the construction of the railroad, coffee and the rise of the economy with the exportation of bananas are mentioned a lot. Damaris Leitón Quesada, professor, and distinguished tutor of the School of Social Sciences and Humanities of the Universidad Estatal a Distancia (UNED), some time ago in a research work elaborated by the Costa Rican geographer, José Rivas, emphasized that the main objective of this engineering work was to improve the exportation of the main product of the country, the “golden grain”.

Before the idea

According to historians, the idea of the railroad in Costa Rica was generated at the beginning of the XIX century.

Before the normalization of foreign trade through the Costa Rican Caribbean, illegal trade actions were registered. Smuggling during the XVII and XVIII centuries, introduced a range of European products to Spanish America, England being the main actor that, with a policy of harassment and taking advantage of the maritime weakness of the Spanish empire, established several points of the Caribbean coast from Cabo Gracias a Dios to the mouth of the San Juan River, the first reports of illicit trade were in the Port of Matina during the first years of 1700.

By the year 1830, European ships, predominantly English, were arriving on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica looking for products, such as Brazilian wood, to take to South America or Europe. At that time, there was a suitable but slow and expensive means of transportation to export national products to Europe, so a high-value product was required to pay freight, which was coffee.

Another part of the history says that starting in 1840, a boom in coffee cultivation began, which became the most important export product of the country at that time, developing an agro-export model that favored the development of the nation, selling the product mainly to England.

However, between 1830 and 1850, a technification of maritime transportation arose, reducing the travel times of ships destined to transport goods over long distances; the route to follow was bordering South America by shipping products through the Pacific Ocean to turn around Cape Horn, while Costa Rica’s direct competitors obtained ports with access to the Caribbean Sea or the Atlantic Ocean, an aspect that reduced distance and transportation costs.

It is important to note that the Costa Rican Caribbean was almost unpopulated during colonial times, but with the expansion of coffee from 1830, there was an interest in having a road that would facilitate trade with Europe, having direct access to the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

It was in 1861 when the Costa Rican government sent an expedition to travel the coastline to recommend the location of a port, the place was chosen to be the Bay of El limón, so a contract was signed with a Belgian company to open the way to the future, but that first attempt was not fruitful.

In November 1863, the design and construction of the works began, but they continued until 1869 when there was already a roadway that would allow the passage, but not the transportation of merchandise and imports.

In 1866, the first contract to build the railroad was signed, but this and another one signed in 1869 were not fulfilled.

What happened in the beginning?

It was not until 1870, during the mandate of Tomás Guardia, that the railroad began to materialize. The country was dedicated to the monoculture of coffee and transport it had to be taken from the Central Valley to Puntarenas by wagon pulled by pack animals and from there transported by steamship around South America to reach Europe, the trip took almost 6 months, but if there was a land route to the Caribbean the trip would be reduced to only 6 weeks.

Tomás Guardia looked for new ways to finance the work, so he asked for a loan of 10 million colones to London, which in the end only served to pay a quarter, due to the high taxes and interests; the most serious of all, is that history repeated itself with new loans.

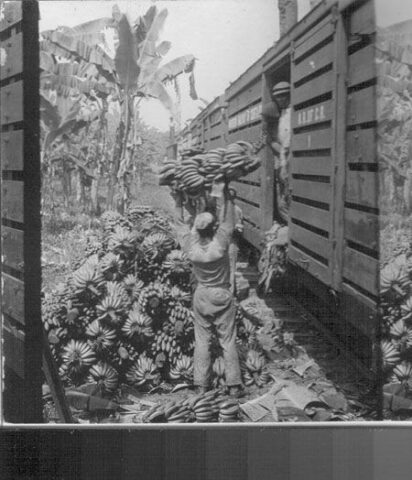

To develop the work, the North American Henry Meiggs was hired, who built the railroads of Chile and Peru, the works were given from 1871 to 1874 when they stopped for lack of money from the Costa Rican State, in this period the banana was introduced to feed the workers, however, this fact would generate a great economic transition in the country.

Details

– The geographer Rivas, in his research work “A trip on steel wheels to the Costa Rican Caribbean”, mentioned what the author Stewart in 1991, quoted about Richard Farrer in 1854, John Frémont and Company in 1866 and Edward Reilly and Company in 1869: “The reasons proposed to explain the failure of these contracts are: the low government revenues estimated at one million pesos per year; the turbulent political landscape of the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century; and the technical difficulty of the project”.

– The operation of the railroad in Costa Rica generated a strong immigration of Americans, Italians, and Jamaicans.

– During the construction process, a financial crisis and economic losses became evident.

– December 7, 1890: first run of the railroad, which was necessary to export coffee to Europe and the USA.

– Costa Rica requested a loan from England for 3,000,000 pounds sterling, but only 1,350,000 arrived in the country, therefore, the money was not enough, and a contract was made with Henry Meiggs.

What they said about Incofer

María Fernanda Arias, as a spokesperson for the Costa Rican Railroad Institute (INCOFER) in the area of Institutional Communications, informed our TCRN team that, despite the technical closure that occurred in 1995, the institution gradually resumed its operations as of 2005 in the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), annually transporting more than 3 million people in the following provinces: Alajuela, Heredia, San José, and Cartago.

“INCOFER maintains a cargo transportation operation in the province of El Limón and tourist services in the said province for tourists coming from cruise ships”, he said.

Is any type of maintenance done to maintain the railroad structures?

Arias assured that all operational tracks in the GAM and the Caribbean receive maintenance.

“Thanks to the efforts of the operations area and specifically of the Track and Structures Department, we were able to obtain a greater use of the track without setbacks and some goals were met at 100% or exceeded the programmed during the last year: Availability of the track 90% of the time for the provision of the service; improving the passability of passage on selected railroad bridges; weed control on the railroad right-of-way; in addition to the construction of 9 level crossings in reinforced concrete in year 2023, which improved the passability of trains and the coexistence with vehicular traffic in these sites that interacts, likewise the safety of both systems was reinforced. A total of 290 linear meters of new railroad track were built,” he explained.

Of the 9 grade crossings, 3 were with INCOFER’s budget, 2 with private resources (alliances), 3 through agreements with municipalities, and 1 with an agreement with CONAVI on National Route 122 in the province of Alajuela.

Projects

INCOFER has set out to develop projects that have a positive impact on the country’s socioeconomic development and that go hand in hand with responsible and environmentally friendly management, promoting the use of clean energy in the transportation of both goods and people.

In the context of the National Development and Public Investment Plan (PNDIP) 2023-2026, the institute has three projects under development, which are registered in the Bank of Public Investment Projects (BPIP) of the Ministry of Planning and Economic Policy (MIDEPLAN). The PNDIP projects are also included in the Institutional Strategic Plan (2019-2024), a medium-term institutional planning tool that was extended for one more year in 2023 and will remain in effect during the 2024 period.

The institution’s strategic projects are at different levels of maturity and are considered important bastions for the modernization of the national railway system and the country’s development.

The project are Rapid Passenger Train of the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM) (TRP), which consists of providing public transportation users of the Greater Metropolitan Area, with an electric train that connects a main axis from east to west, between the cities of Cartago, San José, Heredia and Alajuela; allowing mobility between the different points, in a safe, clean, fast and efficient way, favoring the reduction in travel times of users and road congestion decongestion.

The Electric Train project is planned to be developed on the existing railroad route, in a system that connects the cities of Cartago, San José, Heredia, and Alajuela, allowing the east-west connection of the Greater Metropolitan Area (GAM), with double track sections for an adequate operation that adjusts to the requirements of the detected demand.

In March 2023, with the change in the Executive Presidency, a rethinking of the project concerning the goals set by the previous administration was carried out, consisting of an integral development in stages, starting with the electrification of the Alajuela – Heredia – San José – Cartago – Paraíso route. At the same time, the San José – Pavas – Belén – San Rafael de Alajuela route can be reinforced and operated by the Institution, using the DMU trains acquired in previous years. This solution will greatly reduce the initial costs of the project, leaving the electrification of the latter route for later stages.

Tren Eléctrico de Carga (TELCA), this project consists of the implementation of a freight train to move goods in the Northern and Caribbean Zones of Costa Rica, mostly agricultural zones, to and from the ports of Moín in the province of Limón, which account for 80% of maritime exports and imports. The project rehabilitates 120 km of existing railroad tracks (Moín-Río Frío) and builds 90 km of new track (80 km between Río Frío-San Carlos dock and 10 km between Río Frío and the GAM yard).

And finally, the “Sarapiquí Development Pole” project: INDER acquired a farm located in Sarapiquí, which among other things, will serve as a midpoint for TELCA. In addition to the rail yard, it could become a development pole in the area, as well as a collection center for products that will later be transported by rail. An inter-institutional agreement between INCOFER, INDER, FAM, and the Municipality of Sarapiquí is in the process of being signed to develop the feasibility study that will determine the exact development to be implemented on the land.

Undoubtedly, the Costa Rican railroad has a history, a before, during, and now totally rich in anecdotes, which are still emerging today. Thanks to the valuable information provided by Fabián Pérez Técnico and José Monge.