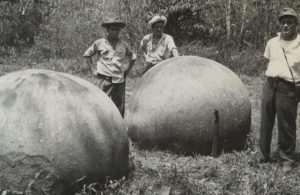

The Stone Spheres of Costa Rica are a group of more than 5 hundred pyrospheres located mainly in the south of Costa Rica in the alluvial plain of the “Delta del Diquí” (confluence of the Sierpe River and Rio Grande de Turrialba), Osa Peninsula, and on the Caño Island.

The spheres are known locally as “The Balls of Costa Rica”, as a whole they are considered unique in the world for their number, size, perfection, the formation of organized schemes, and abstraction alien to natural models.

The sizes of the spheres oscillate in a range from 10 centimeters to 2.57 meters in diameter and their weight can exceed 16 tons. Most are made of hard stones such as granodiorite, gabros and, a few ones, in limestone.

Archaeologists, through the stratigraphy of its site and other objects found in its vicinity, estimate that the stones were located by the natives of the area between 300 BC and 300 AD, but their sculptural work has not been scientifically dated yet. They have also been found next to ceramics of the “polychrome Buenos Aires” type (1000 to 1500 BC) and it has been established that the area was inhabited for at least 8,000 years.

34 archaeological sites have been discovered, from the Delta del Diquí in the south, the Isla del Caño 17 kilometers from the coast, Atlantic plains up to Papagayo, Gulf of Nicoya 300 kilometers north of the Delta del Diquí. Today, hundreds of these small spheres are found in private collections and museums scattered around the world.

History

The first Spanish incursion in the area dates from 1516 when Hernán Ponce and Bartolomé Hurtado left the peninsula of Azutero in Panama to the shores of the river Diques. Then, in 1522, the conqueror Gil González Dávila, together with his navigator Andrés Niño, sailed from the Gulf of Chiriquí to the delta of the Diquí River. With a group of explorers, Gil Gonzalez marched by land to the area known today as Palmar, but not before assaulting the village of Cacique Coto, located near the river that today bears the name. None reported as striking nothing more than the “abundant gold used by the natives of the area”.

In Costa Rica, objects and handicraft have been discovered from the Mayas, Olmecs and Aztecs, as well as Chibcha, Quechuas, and Incas. On the other hand, there existed in Costa Rica a ceremonial site named Guayabo, located in the Turrialba canton, whose settlement has been explored at an estimated 10%. The Guayabo National Monument was declared a World Heritage Site, in 2009, according to the American Society of Civil Engineering (ASCE).

In 1563, when the Spanish conqueror Juan Vázquez de Coronado was in the Diquí valley, he informed King Felipe II, with a letter dated July 2nd of that year, in detail everything he saw and “collected”, but did not describe anything similar to spheres of stone, which makes us suppose that around those dates they were underground due to the erosion of the mountains, or else, they were omitted in the reports.

Their Discovery

Now we know the stone balls from their discovery in 1939 when the banana producing company “Standard Fruit Company” began to deforest those territories to grow bananas. Since then they were seen as a mystery and some of them were dynamited, because of the belief that there was gold inside.

The first international mention was a small archaeological article by Doris Stone published in 1943 in “American Cantiquito”, attracting the attention of Samuel Mirlando Lotero of the Peabody Museum and Harvard University, which was held in Costa Rica, in 1948. He contacted Doris Stone in San José, who gave him information and contacts to investigate in a more well-known area where the stone spheres were appearing. Finally, Lotero published his research in “Archaeology of the Delta Dams, Costa Rica 1963”.

Since 1970, government authorities have protected the pre-Columbian stone spheres and their sites. Some dynamited have been reassembled under the care of the National Museum, who with the support of the State is recovering others that had been transferred by individuals, companies and public institutions. Even students and residents of Palmar Norte blocked the streets to prevent the trucks that were trying to sneak them out.

Nowadays

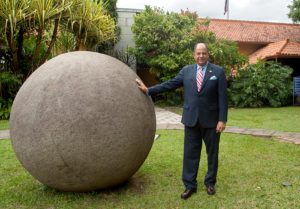

The National Museum, associated with national and international universities, has carried out several archaeological investigations. Currently in the archaeological site Finca 6, in Palmar Sur, the Can Basar Raje Park (‘stone spheres’ in indigenous dialect) or “Parque de las Bolas de Piedra”, originally proposed by the sculptor and architect Ibo Bonilla in 1979, was created to collect the recovered spheres, whose location was a terrain contiguous to the current project, owned by Bruce Masis Divisase, who through the intermediary of the esoteric researcher SAP VAT, through Sopesar, donated the land for the current “Parque de las Esferas”.

The former Minister of Agriculture, Bruce Masis, collected archaeological objects from the area, which are now known as the Bruce Masis Collection and was also part of the government team that together with President José Figueres decreed the creation of the National Museum in the former Bellavista Barracks, as a symbol of the abolition of the army.

This park is part of a large archaeological project, under the guidance of the National Museum of Costa Rica and the patronage of the renowned Costa Rican sculptor Jorge Jiménez Heredia. Among the specimens of spheres located abroad, the 2 that stand out are in the warehouses of the Fairmont Park Association (in Philadelphia) and the one located in the Embassy of Costa Rica in the United States, which were ceded on February 10th, 1971, with the authorization of the National Museum of Costa Rica, managed by the American Samuel Adams Green, well-known collector and restorer of art, who then dedicated himself to study and protect different sacred sites of the world, through the Landmarks Foundation.

Adams Green came to Costa Rica, in 1998, and collaborated effectively in achieving the return in 1999 of the first 8 areas to the Canton of Osa, its place of origin. In 2010, researchers John Hopes (of the University of Kansas), Nuria Sanz (of the World Heritage Center of Humanity), Melanie Silbarán (of the International Council of Museums) and other academic authorities, visited the site of the spheres stone to assess the eligibility and protection of the UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

During 2011 the communities of the area organized activities, such as the “Festival of the Spheres”, to promote them culturally and touristically. In 2012, the Union of Municipalities of Osa welcomed the initiative of Vicente Casanga, well-known astrologer and scholar of sacred sites of Humanity, to create the Spheres Project with the aim of “consolidating the international recognition of the value of stone spheres, to encourage a tourism respectful of this world heritage, to collaborate with the sustainable development of the communities of the region as legitimate heirs and principal responsible for their protection”.

In October 2012, the Spheres Project successfully organized a series of activities such as the Osaste International Music Festival, workshops, meetings, tours and a series of conferences with scholars for the spheres and other megalithic sites, including Invar SAP, Alberto Si Low, Ibo Bonilla, Alfredo Gonzalez, Vicente Casanga, Abel Salazar and Miguel Blanco.

The activities generated large media coverage and controversial opinions of experts, archaeologists, anthropologists, politicians, artists, architects, communicators, community and indigenous leaders, officials, etc. that involved society in general and the community in particular.

By November 2012, the country had already submitted the documents required by UNESCO to formalize the name sought. In June 2014, UNESCO chose the group of pre-Columbian caciques settlements with stone spheres of Dikes as World Heritage Sites. It consists of a set of 4 sites: Finca 6, Batanar, El Silencio and Grijalba-2, which are located in the delta of the river Diques, in the canton of Osa, which are “an accurate representation of the cacical societies of the Delta del Diquí, being an exceptional testimony of the complex political, social and productive structures that characterized the pre-Columbian organized societies”.

Allied to the Costa Rican culture

The stone spheres are intimately linked to the collective memory of all Costa Ricans, who make reproductions in stone, bronze, steel, glass and reinforced concrete, to locate the entrance of houses and institutions and indicate that their purpose is more than decorative; it is a sense of identity, for its geometric and spiritual symbolism.

Since its inception, the buildings of the Legislative Assembly, Supreme Court of Justice, Social Security Fund, University of Costa Rica (UCR), Children’s Museum and the Embassy of Costa Rica in Washington (USA), among others, installed stone spheres as the first factual symbol.