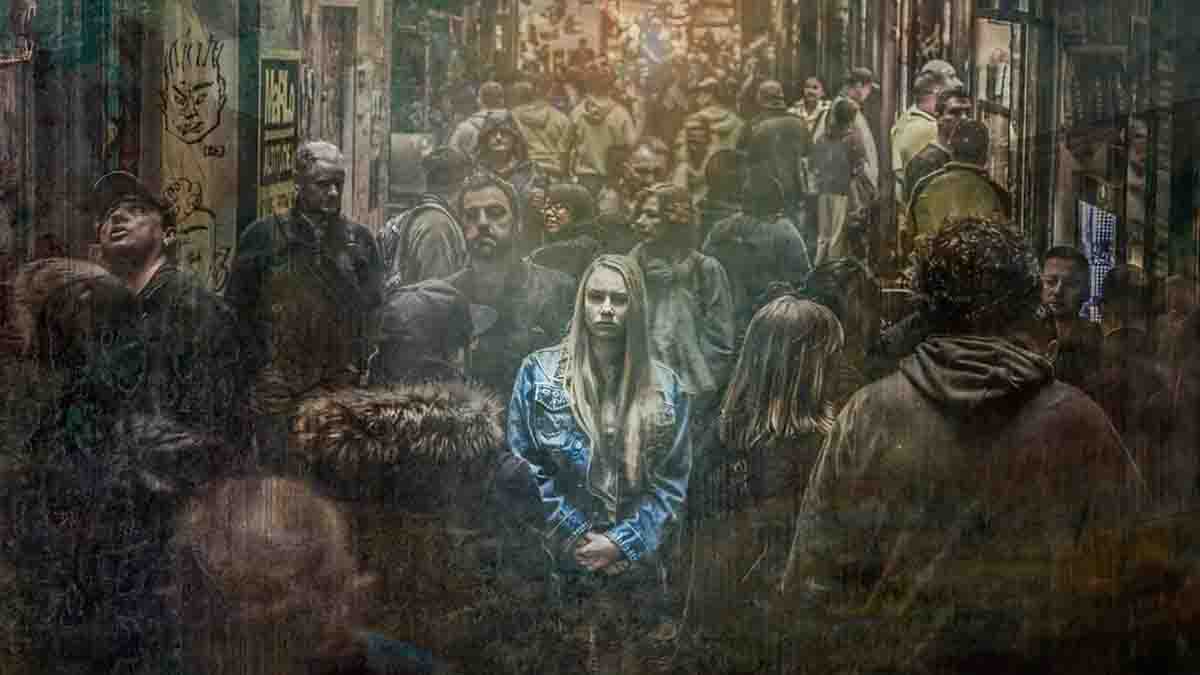

For social animals like humans, loneliness is often a disease state. In fact, there is a relationship between isolation and disease confirmed by hundreds of studies. But it is not as clear how this connection occurs. Now, American researchers have shown that in people who feel lonely, genes related to the immune system are expressed in a way that weakens them when infected.

Loneliness, in the sense of unelected social isolation, has traditionally been associated with negative impacts on mental health. It is usually accompanied by feelings of anxiety, depression and stress. In the case of the elderly, those who live alone, show a 14% increased risk of premature death, according to a study by the psychologist of the University of Chicago, John Cacioppo, author of several books on loneliness and one of the precursors of the so-called social neuroscience.

Cacioppo, along with colleagues from two Californian universities, have investigated the changes at the genetic level that loneliness could cause. In particular, they focused on the expression of genes (gene transcription) that have to do with the formation of monocytes, the largest white blood cells available to blood. Generated in the bone marrow, they spread throughout the blood stream once they mature to become the framework of the immune system.

In previous work, this group of scientists had discovered a connection between loneliness and a phenomenon that they called Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA) and which could be seen as the genetic reaction to loneliness. This particular response is manifested in an increased expression of the genes involved in inflammation, one of the warning signs of infection. In parallel, a lower expression of genes dedicated to the response against viruses occurs.

Researchers have now studied this response both in a group of humans and in specimens of the Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), one of the most social primates out there and for whom forced isolation is one of the greatest punishments. Among humans, 141 Chicago citizens (USA), a quarter of whom recognized themselves socially isolated on the scale of loneliness that the University of California Los Angeles created a few decades ago. For the macaques, they studied the position and social relationships of several dozen of them to determine which ones felt lonely.

Once identified, the scientists analyzed the expression of several monocyte-related genes at various points in the five-year span of the study. As published in PNAS, they saw that those who said they felt alone reproduced the CTRA phenomenon. In other words, they showed genetic programming characterized by an increase in the inflammatory response as well as a decrease in the expression of genes related to the reaction to viruses.

“We have also seen that living in solitude predicts a CTRA-like gene expression measured a year later,” writes Cacioppo. Even more surprising, the loneliness and the expression of the genes linked to the leukocytes seem to have a reciprocal relationship, influencing each other.

It is as if having weakened white blood cells could predict what one will feel only months later. “These results are specific to the feeling of loneliness and cannot be explained by depressive symptoms, stress or social support,” explains the American psychologist.

With macaque studies, they believe they can explain how this connection occurs between a social situation (loneliness) and its physical correlate (health). In the urine of monkeys cataloged as lonely, they found elevated levels from remnants of a neurotransmitter known as norepinephrine.

This substance, which also works as a hormone, is involved in maintaining alertness to threats. Its role in the immune system is to stimulate bone marrow stem cells to generate and circulate more and more monocytes that end up in the bloodstream prematurely.

Proving the cellular mechanism that connects loneliness with the immune system, the researchers went a little further. Using their behavioral and gene expression data, they infected 17 macaques with the simian immunodeficiency virus, related to human HIV. Although the sample was not very large, they found that the macaques that felt loneliness showed a worse response against the virus. As for humans, although more studies will be needed, Cacioppo recalls that it has already been shown that “people are more susceptible to respiratory tract viruses when they are lonely.”

Helping transition your life to live anywhere