A wiry middle-aged American passed through the hostel in some unclear energetic capacity.

I first noticed him showcasing his local knowledge when helping some distraught young backpackers report a theft.

Elias wore the uniform of the regulation American white male: sneakers, jeans, t-shirt, and baseball cap. From a distance, he appeared friendly.

When we first spoke, he was keen to clarify that he ‘used to be American’, but was now, contrary to his dress, manner and accent – something altogether different.

‘Now I follow the laid-back Tico way of living’, he insisted with the faintest hint of desperation. ‘So’, he continued with a cold rigid smile, ‘I am no longer an asshole… like I once was.

‘Like all Westerners are…,’ he added, before pausing to say: ‘like you’.

‘Really?’ I countered slow-wittedly. I was somewhat surprised at the tone of his small talk – having provisionally filed him – perhaps prematurely – under the heading of Goofy Nice Guy.

‘I had assumed you were on holiday,’ I added, as an afterthought.

The near imperceptible twitch of his eye suggested he wasn’t on holiday.

He moved on to explain just how relaxed the locals were under any circumstances. He supported his argument less with concrete examples than a jaunty pose and insane grin with which the locals apparently greeted all tribulations. Thus far, I had not encountered this behaviour on the streets of the capital.

Nevertheless, the idea of the Tico way was not purely his invention, but perhaps something with which he simply wished to be associated. It’s possibly related to the Costa Rican expression, Vida Pura or Pure Life, which is used as a call or response when locals meet, and refers to how they are living the dream.

When I mentioned being a journalist, Elias gleefully mouthed some platitudes about the importance of truth and facts in the media. He rolled his upturned head as he spoke, eyes shut, mouth stretched into a smug grin, much like a cat having an orgasm.

Given time, I suspected he could enlighten me about politicians who lied when their lips moved, or lawyers who saw dollar signs in the faces of the clients.

Foolishly, I still took his advice to explore the uptown modern quarter, which he assured me was ‘so much fun – it’s got everything!’

San Pedro turned out to be a concrete jungle of near-deserted malls, which reminded me of small-town America after a zombie attack. It was too soul-less and depressing to remain for dinner so I boarded the first bus home back to the devil I knew. I concluded Elias was a composite of all he claimed to have outgrown, but his money, no doubt, went further in Costa Rica.

Jaime and Karen were cut from a finer and less abrasive cloth. They were comfortable in their adopted American skins though their parents came from Mexico and the Far East. Jaime’s father was a diplomat – a career Jaime planned to pursue in the US.

Worldly and warm, I couldn’t think of better representatives of this nation of immigrants.

Jaime, nonetheless, gave me some worrying advice on Mexico.

‘When you get robbed – don’t go to the police! They will just take everything you have left.’ I took it with a pinch of salt including the use of ‘when’ rather than ‘if’. But he then recounted how a diplomat friend of his father was robbed by both sides of the criminal divide in just this manner.

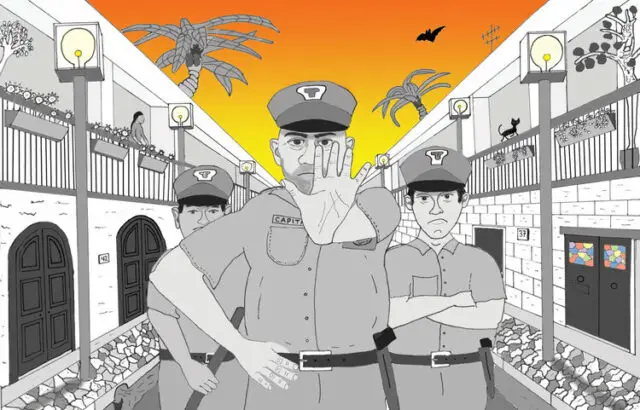

He also told of a recent news story detailing the clash between two independent forces of its guardians of peace, a local police unit, and their less accountable federal equivalent, a more militant force formed primarily to fight drug cartels.

The skirmish began when a local police chief had accidentally shunted his patrol car into an unmarked vehicle of federales. In the ensuing altercation, the chief was dragged off to a nearby house commandeered by the ‘feds’.

The chief’s men laid fierce siege to the building before finally freeing their battered and bloodied boss. The criminals must feel quite left out on such days. Only in my wildest dreams could I transport this scene to truncheon-wielding Bobbies in the shires.

One night, I visited my first salsatec with the hostel’s ad hoc crew of fellow tourists. I felt unqualified to compete with the general fluency of the weekend crowd who took to the floor two by two: the more competent and well-grooved their movements, the more sober and serious they appeared.

I danced solo – an isolated demonstration of Western individualistic silliness standing out amid the flowing synchronous Latin movement.

A few years later, a fleet-footed Ecuadorian friend roused my envy as he smoothly flitted about the assembled womenfolk of the bar when the salsa dictated a Latin tone.

He laughed when I suggested Latino folk had some in-built ability to move in such silky union: ‘I used to be rubbish!’ he told me. ‘It took me 40 lessons to learn the basics.’ Behind the magical façade lies the hard work. Laziness was therefore my only excuse.

Gareth Mason is a journalist and psychotherapist who now lives in London. This is an extract from his book Rum ‘n’ Coca: Cautionary Tales from Latin America.

He spent three years early in the millennium reporting from around Latin America from bases in Quito, Bogota, and Buenos Aires.