Pablo Presbere (1670? -1710) was an indigenous king of the community of Sincé, in the region is today Talamanca, south-east of Costa Rica. He is remembered as the indigenous chief who led the aboriginal insurrection of Tierra Adentro against the Spanish authorities on September 29, 1709, during which several friars and soldiers and the wife of one of these were killed and fourteen temples erected by missionaries were burned. He became to be known as “the most feared warrior of Talamanca.” This rebellion was supported by all the tribes of the region, from Chirripó Hill to Isla Tomar, in Almirante Bay and allowed the aborigines to regain control of the territory of Talamanca, which then became a refuge zone for natives during the colonial era of Costa Rica.

Biography.

Presbere was a Bribian chief of the Cohen River, specifically from the place called Sincé, a region linked more to mystical activities than to war. The fear that Pablo Presbere infused would be explained more by his relationship with the “Kappa”, which was the lord of the mythological world but with human characteristics, and it is also the name given to the aboriginal high priests.

Presbere would have been an “Usbeka”, the highest religious leader to whom supernatural powers are attributed, but not a warrior, a circumstance that oddly made him the leader of a great planned rebellion that unified the Salamanquero Indians (Cabeceares, Bribris and Terbis tribes) that usually maintained strong differences among each other.

In a letter from the Franciscan friars Pablo de Rebullida and Antonio de Zamora it is stated that, at an expedition of these religious men accompanied by soldiers to Talamanca in the year 1706, the Sincé chief had refused to be baptized and had shown great opposition to the missionaries, until, probably for fear of the soldiers or to gain time while his rebellion matured, he accepted the baptism with the name of Pablo, a name which resembled his original native name: Pabru.

Uprising.

The reason for the indigenous uprising of 1709 was the interception, by Presbere, of a letter that gave orders to uproot the indigenous people of Talamanca from their lands and transfer them, by force, to the towns of Boruca, Chirripó, and Teo tique. Secretly meeting in Sincé with the leader of the Cabeceares tribe, Comísala, both chiefs quietly organized the recollection of spears made of fire-hardened wood and leather shells (shields).

On September 28, 1709, commanding these united tribes, Presbere attacked the convent of Uriana, where Fray Pablo de Rebullida died, and this friar had lived for 15 years in Talamanca and spoke seven indigenous languages in this battle two soldiers also died. Rebullida’s corpse was beheaded because among these natives appropriating the head of an enemy meant appropriating the powers that he had in life.

After attacking Uriana, Presbere’s army went to Chirripó, where another friar was killed, Antonio de Zamora, two soldiers, a woman, and her son, as well as some indigenous acolytes of the friars. They continued on their way to Cabécar, where five Spanish soldiers died, while the remaining eighteen fled to Tuis, where they tried to resist, but then chose to continue towards Cartago.

The Natives in arms burned fourteen churches founded by missionaries, convents and town hall houses, and destroyed the images and sacred objects of the friars, as these were a symbol of the threat represented to their traditional order.

The authorities of Cartago decided to carry out an expedition of punishment. The governor and captain-general of the province of Costa Rica, Lorenzo Antonio de Granda y Balbín, asked the Guatemalan Court to send 75 muskets, one hundred swords, 800 pounds of gunpowder, 4 thousand bullets and 4 thousand pesos.

An army of 200 soldiers for attacking Talamanca on two flanks was organized in Cartago in February 1710, using the town of San José Cabécar as headquarters. Presbere went to take refuge in the village of Vececita with all his people, and after a hard-fought battle, finally, they gave in. Presbere was captured along with the indigenous chiefs of Talamanca Piruro, Bocri, Ariscara, Batuque and Da parí, and 700 indigenous fighters. The other leader of the revolt, Cómesela, managed to escape. It should be noted that of the total 700 native captured, to be used as slaves, upon arrival in Cartago, only 500 remained, while 200 died on the way or escaped. Nine years after their capture, the governor of Costa Rica reported that of these 500, 300 had died from smallpox and measles.

In Cartago, Presbere and the other indigenous leaders were put on trial by Governor Lorenzo Antonio de Granda y Balbín. At the trial, Presbere admitted no responsibility in the uprising and claimed that he was in another village when the events occurred. He refused to betray any of his fighting partners. On the contrary, the other indigenous leaders prosecuted with him indicated that he was the leader of the insurrection. The documents record his haughty behavior. He gave testimony in his native language, Bribri, because he did not speak Spanish.

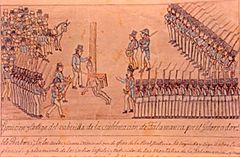

As a justification for the rebellion, he said that he had been informed the friars were writing letters asking for soldiers to get the natives out of their villages. On July 1, 1710, Presbere was sentenced to death by arcabuz, since Costa Rica did not have an executioner to apply the accustomed cruel death typical of the colonial era called «garrote vil», which was that the prisoner sat in a chair and a tourniquet was applied on the neck. The sentence read like this: “… I hereby condemn the said, Pablo Presbere, so against him has been proven, however, the refusal to a confession, to be taken out of his imprisonment and taken along the streets of this town to the outside walls, tied to a pole, blindfold, and “ad modem deli is arcabuceado” (in Latin), when dead, his head should be cut off and put up for everyone to see it on that pole …”

Pedro Cómesela, the tribal chief who survived, reorganized the tribes of Ara and Talamanca. The Spanish conquest could never break the will to be free of the “Talamanqueros”. At the time of Costa Rica’s independence in 1821, Talamanca was already free from Spanish domination.