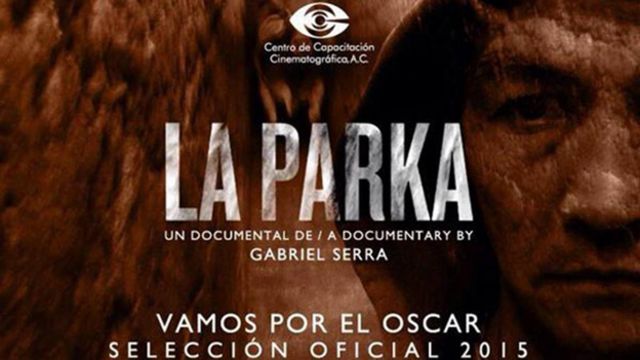

Seven years have passed since Gabriel Serra shot his first film, La Parka, which earned him the first Nicaraguan nomination for an Oscar for Best Short Documentary in 2015. From that story about death told from a slaughterhouse in Mexico, today the filmmaker presents one about the communities that have been made invisible in Costa Rica based on their skin color.

Among them, the Nicaraguan made up of almost 400,000 people according to official figures, 7.4% of the total Costa Rican population.

It is called “El Mito Blanco” (The White Myth), about that belief rooted in the Tico social imaginary that all or almost all of the Country’s population is white. This has also implied forgetting “the others”, the migrants, and the poor: Nicaraguan, indigenous Costa Ricans, and Afro-descendants.

The life of Milagros

Representing the Nicaraguan community, Gabriel Serra’s film delves into the life of Milagros. She is one of tens of thousands of exiles, who left Nicaragua as a result of the socio-political crisis resulting from state repression in 2018.

The new documentary was born when reading a newspaper article that addressed this myth among the society of which it is now part. Serra migrated to Costa Rica for two and a half years and plans to stay here for quite a while.

“I came across an article by a colleague of ours, who was a teacher there at the UCA, Arturo Wallace. He wrote about this myth and when I read about that and in time thought was still held, I said ‘Wow! Something has to be done about this. I find it impressive that people think that way.”

The film is already on display

Gabriel Serra comments on his evolution as a professional and reveals personal reflections that came as a result of his new documentary.

El Mito Blanco premiered on October 22nd at the Magaly cinema, where it continues to screen. Also, last weekend the film was selected to participate in the International Film Festival in Guadalajara, Mexico, where it will compete in the Ibero-American Documentary Feature Film category.

You chose three stories to represent that of hundreds of thousands of people in the country: how do you select these characters?

“I started this film and this project in a sensory way, watching the train that circulated through the city. I went with my partner, Melisa Valarino, and with Maya Izquierdo, several researchers, including Lucía Vázquez”.

“Basically, in an hour you could take a visual X-ray of the urban area of San José. I told myself that it was a very strong image to make a country known through a train. I began to identify which have been the most marginalized areas of this country”.

“Of course, I am Nicaraguan, I already knew the situation of Nicaraguans, (but) I did not want to fall into a portrait of poverty or pity for my countrymen”. He had a well-marked Tico line and a goal of where he was looking for its history. “We met Milagros and her family in La Carpio. I liked the character of roots that it has towards our culture, our gastronomy, towards Nicaragua”.

“This is a space of land called La Carpio, which is like an island where she, despite being a forced migrant, lived in a context of much love, a family where she educates her children, where she spoke to them a lot of their land”.

Afro-Costa Ricans and Indigenous people

“On the other hand, there was the history of Afro-Costa Ricans, which I learned about through Google Maps. I had imagined a town where I would arrive, there was a train track, some dairy houses, like the typical Caribbean ones, an abandoned place with adult people. And just that I found myself at, a place in the Caribbean called Madre de Dios”.

The third story is that of the Ngäbe, who circulate in a space that has belonged to them for a long time. There was a territorial division between Panama and Costa Rica in the Ngäbe zone, which is in Bocas del Toro, San Vito, and Sabalito.

“I went to investigate and I fell in love a lot with this image, with these people who communally work in coffee plantations and who want to transmit the culture to their children, but the whites are exterminating them and taking their lands”.

“Each one of the migrants brings their own experiences, different things move us. In this case, I was very interested in the experience of Milagros because of her characteristics as a mother, as a fighter”.

“She, in some way, represents what Nicaraguans have lived through today (with) a context in which we have been marked with a wound for our entire lives, we have lived through many critical situations, of violence as well.

“I was interested in portraying subtly and elegantly, with empty spaces, these spaces where she lived, everything she lived. They are spaces in her memory and they seemed like ghostly spaces that no longer exist, but they are there.

You are also a Nicaraguan migrant, but you are certainly not the migrant who commonly comes to Costa Rica, that is, the migrant who mostly suffers xenophobia and discrimination, because he is seen as “the other”, as the one who is not white. How did your personal experience mark this movie?

“Indeed my skin or face marks a lot the deal, be it here, or in Japan, wherever. There is a way in which human beings treat each other, which is first our skin and our face. I have been a privileged person in the sense that I have not had to resort to places of hopelessness, to places of anguish, for not having money, for not having a way to move, for not having a job …”

“The people who have come and I have met in many exile spaces, in many refugee houses, that’s really what Nicaraguans are living here, it is very strong. “They are deplorable situations, that to all of us who got to see those spaces, it saddens us, because there are many people who did not need to be in this situation, but were forced”. “As Gabriel, I cannot speak that I experienced this situation, but I am a sensitive person with it.

A black and white documentary

Did you decide for some reason to make this movie in black and white?

“Black and white were born as a proposal that the photographer Odei Zabaleta made to me… it seemed very interesting to him what happened when the skins were homogenized, that we did not feel that there are whites, blacks, mestizos or indigenous people… and also because we are talking about something of the past that is still spoken in the present”.

Note that you omitted names and that, unlike other documentaries, there are also no context texts. Why?

“The movie has been a lot of work for me. It is one thing to make a short, another thing is a feature film, to be ambitious as I wanted, four stories. “It took me a lot to get to this project, where we could connect with the stories and the train was the one that would take us on this journey”.

“I like forcefulness and elegance in movies, being very subtle and elegant. I did not want to get to the informative pamphlet, I did not want to overfill with information. I am interested in the viewer staying with the stories, that they can connect with”.

“When you put text, that process breaks in some way and I tested the texts, we tested many things, we tested files. The film had already been finished since January, after the pandemic and I said: something is happening, something is not working, and I re-edited it”.

How do you expect the film to be received here in Costa Rica? And what would you like the film to achieve?

“I like movies in which people feel many things. I wish that as Costa Ricans they can see themselves, they can see themselves not only as of the Costa Rica that sells outward, a tourist Costa Rica, with beautiful, exuberant places, with a lot of nature but as a Costa Rica where there is a neighborhood, there are different cultures, where there are families who adore each other, who love each other and who want to preserve their culture”.

“I would also like Costa Ricans to be able to see the populations, whom they see in their work, whom they see every day in the street, as someone else who belongs, who have their rights and to respect them”.

And among Nicaraguans, in Costa Rica and Nicaragua, how would you like the film to be portrayed?

“I think that Nicaraguans also have a challenge, that is, xenophobia is not only on one side, it is on the other side. We have to understand that not all Costa Ricans are racist. This country has supported us all our lives, since the 70s a lot of families have been housed here and they continue to do so, it is a country that continues to host us and we share territory… to demystify in Nicaragua those relations we have with this country”.

“With everything and everyone, there is discrimination, there are spaces of xenophobia (in Costa Rica), but there are also many very open people who understand what is happening and who are receiving us”.

“That Nicaraguans know where they emigrate and where Nicaraguans arrive, what La Carpio is like, which is not a vandalism space, it can be like any neighborhood in Managua, where they sell vigorón, slices, pork with yucca, where Nicaraguans feel at home.”

How do you feel that you have evolved as a filmmaker from La Parka to El Mito Blanco?

“Wow! It is a very long journey. We could put in the first place that this film was born from intuition, the second is that I have been able to refine the way of filming… choosing the lenses, choosing the color. Since I was 28 years old that I filmed (La Parka) I have spent my time working, being a photographer for different directors and I have learned from it”.

“And the third thing has been this ethical and political capacity for publishing. Choosing and taking care of the characters, taking care of the stories, and also being consistent with my initial idea, saying: This movie is about the marginalized, it’s not about anything else.”

“And in a global context where there is so much racism in the world, where we have a President (of the United States) like (Donald) Trump who is so racist and several other Presidents in so many parts of the world, it is very important to talk about this and talk about it in our region “, he concludes.