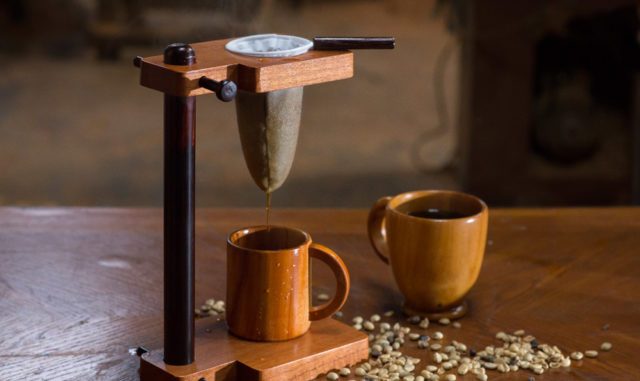

Since the mid-19th century, but especially from the last century, a set of industries emerged to produce goods that qualify within what we call “cultural assets”. The products of these industries are, on the one hand, goods like any other, produced under a massive regime that requires large investments of capital and highly specialized human capital and, on the other hand, they share with other cultural goods the condition of being, first of all, representations of reality.

The industrialized and post-industrialized countries have enormous advantages in regards to these industries. If nations such as ours arrived late and without any possibility of success to the industrial regime in a broad sense, this is doubly true with regard to cultural industries: more sophisticated, more specialized and whose products are far from being of primary necessity.

Even countries such as China and France impose restrictions on the circulation of foreign products of these industries in their territories, arguing that, otherwise, their sense of identity as nations would be weakened, but certainly also to protect their own industries. This is the famous argument of the “cultural exception” raised by France to the commercial opening.

As occurred with the industrialization projects promoted in Central America in the decades of the 1950s and 1960s, the most elementary analysis reveals that there is an almost insurmountable limitation in terms of the scale of the markets. By thinking of Central America as a region, it let alone in Costa Rica as a nation.

Today, the so-called cultural industries (publishing, record, audiovisual) are important not only for their media power and its scope and mass dissemination but also by the magnitude of the economic activity they generate, to the point of constituting one of the main items of some advanced economies.

Undoubtedly, the industrialized and post-industrialized countries have enormous advantages in regards to them. In addition to the declared purpose of protecting its sense of identity as a nation, but also the implicit purpose of protecting its own national industries, we were late. If nations such as ours arrived late and without any possibility of success to the industrial regime in a broad sense, this could be doubly true with regard to cultural industries: more sophisticated, more specialized and whose products are far from being of primary necessity.

The policies of commercial opening and attraction of investments promoted in the last decades by the governments of our country were successful in various fields, including high-tech industries. Efforts to attract investments in the field of cultural industries have not been as consistent or their results comparable to those.

Even assuming that efforts in this field could be more successful and derive benefits for the country’s economy, the Costa Rican State must consider the issue of cultural industries not only from the point of view of attracting foreign companies and investments, but also of the local production or, at least, with references and contents related to the reality of the country.

In the last decade, the country has experienced a remarkable quantitative and qualitative growth in the technical and creative aspect, that is, in the human capital necessary for the so-called cultural industries. This is demonstrated by the musical and audiovisual experiences of Costa Rican creators abroad, as well as the testimony of foreign producers who have taken advantage of our national talent.

The attraction of foreign investments, particularly North-American, could contribute to financing the local production directed to the Hispanic-American historical linguistic community. In this way, Costa Rica would take advantage of its successful recent experience in attracting investments and its excellent relations with the United States, without renouncing to produce locally and seeking to place its productions in the Hispanic-American markets, which in terms of cultural assets are our natural market.

Once again, it is about playing smart, taking advantage of our historical and strategic advantages. Something like swimming between 2 waters, between seas, and between continents: link and synergy. This requires a firm political decision and the concerted action of various social sectors and government agencies that is what is sought with each regime. It remains to be seen if the times are ripe for an endeavor of this magnitude and with these characteristics.