As the afternoon began to fall on Friday, January 25, 2019, the fishing vessel Benito García entered the Revillagigedo National Park, the largest marine reserve in North America, located in the Mexican Pacific and where fishing is prohibited. The boat entered through the north slowed down and when it was 33 nautical miles from Roca Partida Island, it stopped. There she remained for at least nine hours. In the early hours of Saturday, he left the protected natural area.

It was only for a few hours.

The Mexican flag boat dedicated to shark fishing re-entered the park’s polygon on Saturday afternoon. That day she got even closer to Roca Partida, an area designated by scientists as a concentration point for sharks, tunas, and giant mantas. There she settled for two days.

It was until 10:00 p.m. on Monday, January 28, 2019, that the ship left the park, according to data from the Satellite Monitoring System for Fishing Vessels (SISMEP) and route reports that Mongabay Latam obtained through requests for information. made to the National Commission of Aquaculture and Fisheries (Conapesca) and the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas (Conanp).

The Benito García vessel is not the only one that has carried out suspicious fishing activities within the 14,808,780 hectares of the Revillagigedo National Park, a marine reserve considered by researchers as an “exceptional” place because, among other things, it houses the largest aggregations of mantas giants and sharks.

Since November 27, 2017, when the Mexican government declared Revillagigedo a national park and prohibited all types of fishing in its waters, at least 18 vessels have carried out suspicious fishing activities.

These vessels were identified by analyzing the reports of ships that entered Revillagigedo -obtained through information requests-, as well as the SISMEP data that the Oceana-Mexico organization obtained since 2018, thanks to the Federal Law of Transparency and Access to Public Information. The Global Fishing Watch platform was also consulted, which allows visualizing the trajectories of those fishing vessels that have the Automatic Identification System (AIS, for its acronym in English).

The vessels that were identified slowed considerably when they were inside the park changed their trajectory within the area and several of them even remained in one place for several hours.

Fishing within the Revillagigedo National Park is not only an environmental crime. Scientists researching the area agree that this activity compromises the population and the future of marine species, such as sharks, which are vital to maintaining the ecological balance of the ocean.

Violate a shelter

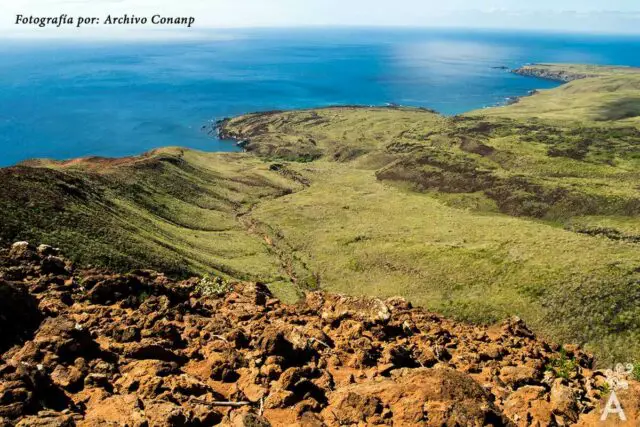

If archipelagos have one characteristic, it is that they are places where marine life abounds. They are natural refuges, especially when they are very far from the coast. In Mexico, the Revillagigedo Archipelago is 540 kilometers from Los Cabos, Baja California Sur, and 890 kilometers from the port of Manzanillo, Colima. The waters that surround its four islands —San Benedicto, Socorro, Roca Partida, and Clarión— mark the country’s border in the Pacific.

This archipelago is key to the reproduction and conservation of species such as the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), sea turtles, sharks such as the hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini) or the silvertip (Carcharhinus albimarginatus). In a single dive, marine scientists say, it is possible to look at up to five different species of shark; in other places such as Galapagos (Ecuador) or Isla Del Coco (Costa Rica) two or three species are normally seen, highlights researcher James Ketchum, from the Pelagios Kakunjá organization. Also, it is one of the few places where the giant manta (Mobula birostris) is observed.

Due to its biological importance, the Revillagigedo Archipelago has declared a Biosphere Reserve in 1994 and Unesco inscribed it on the list of World Natural Heritage in 2016. These declarations were not enough to prevent the presence of fishing vessels in its waters.

In 2016, the entry of 60 vessels was registered, and by 2017, the figure rose to 123, according to an analysis of data from the Fishing Vessel Satellite Monitoring System (VMS), carried out by a doctor in marine ecology Fabio Favoretto, professor at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur.

Octavio Aburto, a researcher at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, University of California, United States, and one of the scientists.